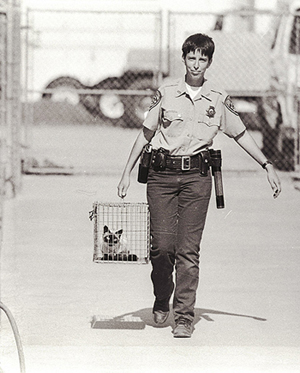

For Community Cats, A Change Is Gonna Comeby Kate Hurley, DVM, MPVM December 11, 2013 This article originally appeared in the September-October issue of Animal Sheltering magazine.  Schmuel Thaler/Santa Cruz Sentinel Back in the early ’90s, the Santa Cruz Sentinel did a profile of my shelter jauntily titled “From Canines to Constrictors with the SPCA.” The picture of me (at right) ran with it, and whenever I happen across the story, I remember the pride I felt in that uniform (in spite of my regrettable cat-carrying technique. Note to former self: Next time throw a towel over the carrier!). I also remember the dedication I felt toward the animals in our care. I know a lot of you will relate to what I told the reporter that day: “I work with people. I like people. But the reason I do this job is because I love animals.” For all my enthusiasm, I also talked to the reporter about the dark side of the job. That year, more than 4,500 animals lost their lives at that shelter. The cat I was carrying had only about a 25 percent chance of leaving alive. Had she been unsocialized, her chance would have been zero. Our policy was to euthanize feral cats immediately, so it would have been my job to march back to the euthanasia room, and perform that sad task myself. And that’s something I did, with the most care and professionalism I could muster, too many times to count. I did this even though I loved cats, even though my nickname as a kid was “Little Kat” Hurley, even though my best friend growing up was an immense tortoiseshell cat named Pussywillow. I did this even though it broke my heart. Why? Certainly not for lack of caring. Indeed, shelters exist because people care. They exist with a goal of protecting animals, preventing cruelty and suffering, promoting healthy, humane communities, and solving the problems associated with companion animal overpopulation. And they—we—have had remarkable success. On a per-capita basis, shelter euthanasia in the United States has reportedly decreased more than 10-fold since the early ’70s. But if you look closer, you’ll see the news is not all good—especially for cats. Although some communities are doing much better, in my home state of California, the odds of a cat leaving a shelter alive are still only about one in four. Across America, outcomes for cats may be improving, but not nearly as quickly as they are for dogs. In some communities, feline intake and euthanasia continue to rise. Why? For the answer to this question, we need look no further than the unowned cats sauntering through the alley behind the gym, loitering by the dumpster at the local fast food joint, or hanging around our own backyards. The Community Cat Gap

Until recently, most sheltering programs simply didn’t focus on the role that unowned animals play in shelter intake and euthanasia. But to educate owners on the benefits of sterilization or training that might help them keep their misbehaving cat in the home, there has to be an owner getting the message. In order for adoptions to reduce shelter euthanasia, the animals concerned have to be suitable for a home environment. Feral and unsocialized cats defy these requirements. Often there is no caretaker to avail themselves of low-cost services or benefit from programs aimed at helping pets stay in their homes. No matter how long the stray holding period, there is no one to come looking for an unowned cat, and the number of unsocialized cats entering most shelters far exceeds the number of barn or alternative homes to be found. And the role played by these cats is far from trivial—in fact, researchers have estimated that the population of unowned or “community cats” missed by traditional sheltering programs might be as big as the population of pet cats in the United States. Gulp. Fortunately, there is great news hidden in this alarming data. Once we understand the role community cats play in shelter intake and euthanasia, we can begin to solve the problem. And we don’t have to wait decades to do it. The fact is that some outdoor-living cats are already thriving in communities. Picking up and euthanizing a small fraction of them doesn’t serve any of the purposes for which shelters were formed. It doesn’t protect the cats themselves. It doesn’t help reunite lost cats with owners. It doesn’t protect other pets, wildlife, or human health. And it doesn’t help control feline overpopulation—if it did, we would have solved the problem long ago, when shelters were euthanizing 10 times as many cats as they are today. Once we recognize this fact, we can just stop euthanizing healthy cats. And we can redirect our efforts at programs more likely to benefit cats and communities as a whole.

|